Exporting H20 Chips to China Undermines America’s AI Edge

Continued sales of advanced AI chips allow China to deploy AI at massive scale.

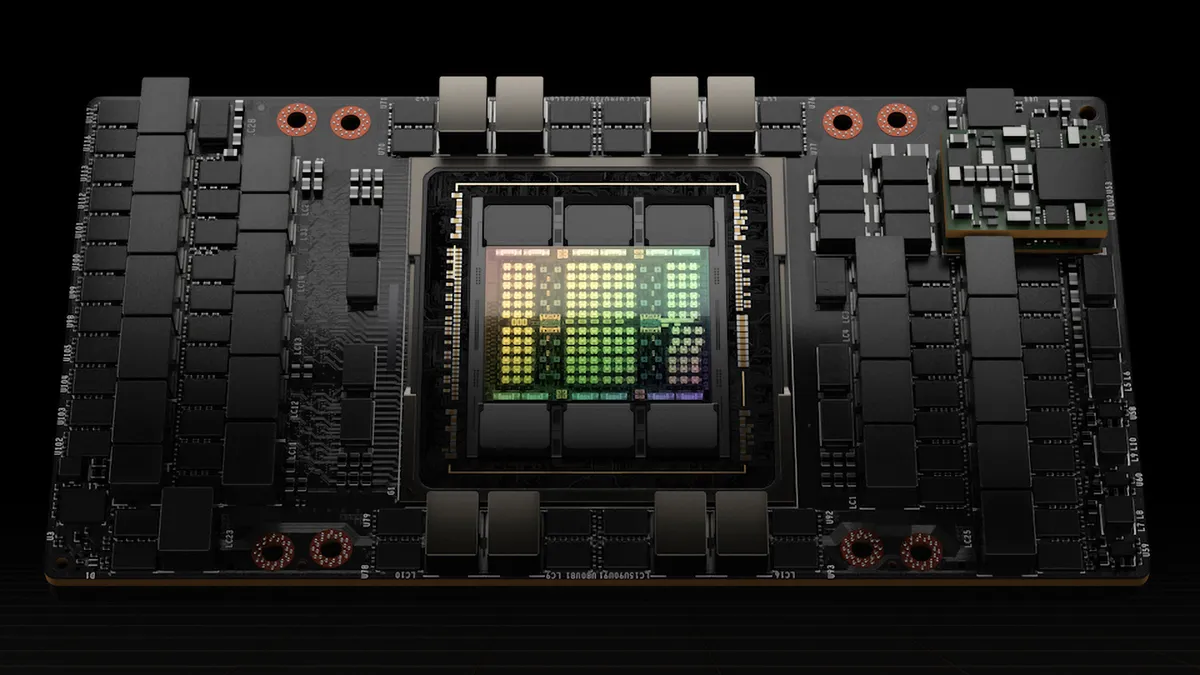

Chips are the backbone of modern artificial intelligence. One chip in particular, Nvidia’s H20, has become a flashpoint. Developed specifically for the Chinese market, the H20 was engineered to avoid existing US export controls while preserving key capabilities that make it highly attractive for advanced AI systems.

National security experts and AI policy leaders have urged the US government to treat chips like the H20 as a strategic asset. And until just days ago, it appeared the Trump administration was prepared to act—moving to block their sale to China.

Following a dinner at Mar-a-Lago attended by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, the administration reportedly paused plans to impose further restrictions on H20 chip sales to China. Sales will continue. Experts argue the decision undermines a policy Trump has championed: to ensure America, not China, leads the world in AI.

Sales of the H20 chip carry significant implications for US AI competitiveness because of a recent shift in how cutting-edge AI systems are developed. Until recently, progress was driven largely by training: using powerful chips to pre-compute knowledge into models. But the emergence of models like OpenAI’s o1 and DeepSeek’s R1 — sometimes called reasoning models — marks a change.

These systems rely more heavily on inference-time compute—the ability to reason dynamically during user interactions. As models spend more time thinking at the moment of interaction, computation demands have surged, both because reasoning models process more per interaction and because they enable more complex tasks.

Additionally, the growth of AI models capable of generating high-resolution images and videos further increases the demand for computational resources.

The H20 is attractive because it's affordable while still being sufficiently powerful. While not Nvidia's most advanced chip, its price-to-performance ratio makes it ideal for scaling increasingly intensive AI services to millions of users.

Chinese access to these chips threatens US competitiveness—not necessarily because it enables China to develop more advanced AI models, but because it improves China’s deployment capabilities, the computational power it needs to deploy models at scale. With a sufficient supply of H20s, China can dramatically increase its capacity to serve more users, including powering significantly more autonomous agents simultaneously. This would allow China to derive substantially greater economic value from existing technology and potentially tilt the competitive landscape in its favor.

The H20 was engineered specifically for the Chinese market, designed to dodge US export restrictions while preserving its interconnect bandwidth.

Want to contribute to the conversation? Pitch your piece.

As Peter Wildeford, cofounder of the Institute for AI Policy and Strategy, explains: “The H20 provides vastly superior bandwidth and latency than what China can produce domestically. China is far from being able to produce this itself—instead, they power their AI by buying hundreds of thousands of H20 chips.”

By allowing China to continue purchasing H20s, this move appears to be reducing US competitiveness. As Sam Hammond, Chief Economist at the Foundation for American Innovation, notes, “President Trump made it the policy of the United States to secure American dominance in AI.”

That strategy relies heavily on restricting China's access to advanced hardware like the H20 and limiting their deployment capabilities. As Hammond explains, leadership in AI depends on four main ingredients: algorithms, data, hardware, and energy. “China and the US are roughly at parity on algorithms and data, with the potential edge going to China, given its weaker privacy laws and centralized data sources.”

He further points out that, on energy, “China added over 400 gigawatts of net new electric power generation to their grid in 2024, a 20% year-on-year increase”, compared to the US, where “net energy production is flat, and our grid is not prepared for significant load growth.”

That leaves compute as one of America’s last remaining advantages in the competition to lead in AI. A nation’s power is directly proportional to the number of chips they have—effectively determining the size of their digital labor force and economic potential.

/odw-inline-subscribe-cta

Without H20 export controls, Hammond warns that “Tens of billions of dollars of the most advanced GPUs now available to China will flow across their borders, and America's leadership in AI will begin to evaporate.”

Nvidia argues that restricting exports would simply accelerate China’s domestic chip development. However, China will go full bore regardless of what the US does. China has already invested billions in building its own chip industry over the past two decades. It’s far from clear that additional export controls would significantly alter this long-term strategic commitment.

Meanwhile, Nvidia’s financial incentive is obvious. The company sold $16 billion worth of these specialized chips in Q1 2025 alone—to Chinese firms including ByteDance, Alibaba Group, and Tencent Holdings.

That commercial interest sits uneasily alongside Nvidia’s public statements. During a recent White House visit, the company embraced “the importance of strengthening US technology and AI leadership.” Its aggressive push to expand sales of H20 chips to China is hard to square with that claim.

Concerns have also been raised that Nvidia has done too little to prevent circumvention of export controls. As Tom’s Hardware notes, Nvidia’s sales to entities in Singapore increased by over 10 times in fiscal 2025 compared to fiscal 2023, from approximately $2.3 billion in FY2023 to $23.7 billion in FY2025. The volume of these sales strongly suggests chips are being rerouted to restricted markets, including China.

Hammond called the suspension of H20 controls “a betrayal of Trump’s own stated policy for American AI dominance”—and one that comes at the worst possible time, as China launches a new $138 billion state-backed fund aimed at bolstering its high-tech sectors, including artificial intelligence.

Yet this decision is still reversible.

The administration could act immediately by sending an “Is Informed” letter—a measure that empowers the US government to notify companies that specific exports pose an “unacceptable risk” of diversion to military or restricted uses.

An “Is Informed” letter to Nvidia—stating that the sale of H20s to Chinese companies violates existing supercomputing export controls—could be sent tomorrow.

See things differently? AI Frontiers welcomes expert insights, thoughtful critiques, and fresh perspectives. Send us your pitch.

The White House is betting that hardware sales will buy software loyalty — a strategy borrowed from 5G that misunderstands how AI actually works.

AI automation threatens to erode the “development ladder,” a foundational economic pathway that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.