In the Race for AI Supremacy, Can Countries Stay Neutral?

The global AI order is still in flux. But when the US and China figure out their path, they may leave little room for others to define their own.

This post was cross-published on the author’s Substack, Threading the Needle

Increasingly, the US-China AI race is taking center stage. To win this race, Washington and Beijing are rethinking a range of policies, from export controls and military procurement priorities to copyright and liability rules. This activity, under the vague banner of race victories, conceals a deeper lack of clarity on strategic objectives. The Trump administration’s AI Action Plan provides yet another entry on what the US strategy might look like — but it shouldn’t be mistaken for an indication of strategic clarity, as US factions are still vying for dominance from decision to decision. All in all, Chinese and US AI strategies are both still nascent. This raises important questions: What will each country decide that “winning the AI race” means? And where does that leave the rest of the world?

The obvious answer to the first question is: whichever great power comes out ahead is the winner. But reducing the answer in this way risks missing a critical point, while disregarding the often-cited justification for the race to begin with: that US AI dominance is essential to ensure AI goes well for the world.

Conventional wisdom in the AI policy space holds that, with regard to advanced AI systems, the policies of the US and perhaps China matter above all else. There is, of course, a way in which that is very true: policy made in the places where AI is being developed has outsized leverage over the entire world. But there is a way in which it is untrue: when it comes to shaping the consequences of advanced AI for people’s lives, the many other nations and economies that do not develop their own frontier systems matter greatly. This is especially true for “middle powers,” the group of advanced economies that are currently leaving their options for AI strategy open: much of Europe, Japan, India, Canada, and more.

This piece looks at the open questions around great-power AI strategy and what they might mean for the fate of middle powers — and, therefore, for global AI outcomes.

A lack of well-articulated win conditions by the superpowers is, to a great degree, the result of ongoing internal disagreement within each. Currently, there are three competing views of AI-race win conditions that, if not always made explicit, are vying for doctrinal and practical dominance.

1. Military victory

It’s not clear how “securitized” the AI race will become. First, both great powers are internally split on how inevitable they think a militarized culmination of the AI race might be. If you assume that advanced AI provides a decisive military advantage (e.g., through its contribution to cyberoffense capability or strategy), you will most likely approach AI as a conventional military resource, seeking to build it before others do.

On that view, a highly securitized environment makes a lot of sense: you want to constrain the opposing power’s knowledge of and access to your own frontier systems, so you jealously guard their proliferation among third parties. That conclusion is especially likely if you suspect that these third parties may smuggle imported chips to restricted target countries (as the US may fear in Southeast Asia), or if you think these third parties may be more susceptible to espionage, cybersecurity breaches in data centers, etc. If you’re seriously preparing for a US-China war fought with AI weapons, hard controls to safeguard frontier capabilities make sense.

2. Economic victory

Winning the AI race may mean establishing economic instead of military supremacy: more like racing to secure oil rather than building nuclear weapons. This is a mercantilist view of the AI race’s strategic dimension, approaching AI as a central resource that determines the flow of the global economy (as oil does now). In this view, a securitized environment makes much less sense: If you’re planning to achieve economic dominance over the other side by selling AI, controls are less attractive. This notion, underpinned by broader cultural considerations, seems to motivate the Trump administration’s just-released AI Action Plan, which provides a blueprint for a market-share oriented view of competing with China on AI.

You might think this is the view that China is operating on for the moment, attempting to undercut US market share and hegemony through open-sourcing near-frontier models. In an economic-supremacy model, leverage is rarely exerted through hard measures like turning off supply or restricting exports altogether. Instead, the dominant country exerts leverage by subtly manipulating the flow of intelligence, akin to how major oil suppliers have subtly manipulated the flow of oil in the past.

3. A hybrid approach

Between the paths of military or economic victory, great powers may strive to expand their spheres of influence. This approach involves treating AI as a strategic trade resource. Export and sale are still strategic levers, but not primarily for the revenue they generate; instead, conditions attached to export approvals are used to create entanglements and alliances, cutting off the adversary’s market access.

In this approach, great powers consign middle powers to exclusive AI-access deals in return for their national resources, manufacturing capacity, etc. If you’re planning to create allegiances and alliances by controlling AI access, leverage-focused export limitations make the most sense.

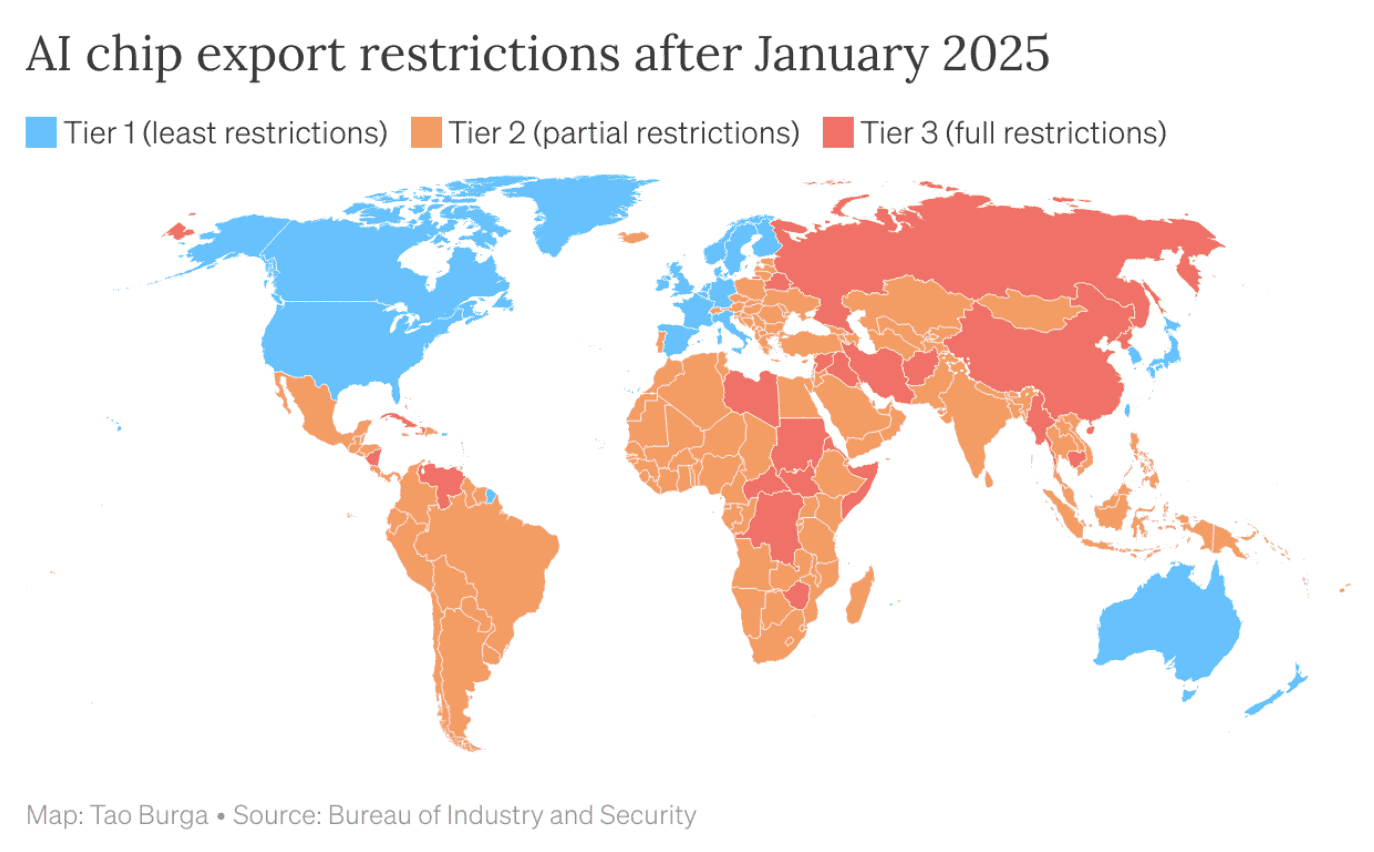

This middle ground has well-established precedent both in the US and in China. It has very clearly been the motivation for the Biden administration’s diffusion framework. In past trade policy, China has strategically deployed infrastructure exports and trade deals to create favorable relations in sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia. There is reasonable debate about the extent to which this has been a shrewd strategy on China’s part, but it seems unambiguous that, throughout the Belt-and-Road initiative, China has learned the value of strategic export leverage.

Great powers are still internally debating which strategy to take. In the US (both within the Trump administration and the broader AI policy environment), we see lively discussion around which of these stances to take. Likewise, China seems undecided between strategical approaches. That said, China is in the slightly less option-rich position of being behind on both compute and models, meaning that it has no realistic way to implement restrictive export regimes just yet.

To make matters still more complicated, grand strategy is constrained by practical uncertainties around the shape of progress in AI capability. Three variables are particularly relevant to strategic decisions.

1. Military usefulness

The question of whether to securitize depends on how useful military applications of models are, compared with their economic applications. We might find ourselves in a primarily military paradigm, where AI systems can be deployed to decisively boost military capability, whether through strategy, cyberoffense, or second-strike prevention. Or we might have an economic paradigm, where AI systems primarily generate strategic value by boosting economic research and development, growth, and production.

In the former case, great powers can get away with a high degree of lockdown of their AI systems. In the latter case, the strategic value of any lead in AI only manifests by diffusing it through an economy, and ideally to one’s allies as well — which is at odds with stringent security oversight.

2. Frontier capability gap

It will matter to what extent the capability gap persists between the best AI models and fast followers. If the best proprietary models stay ahead of widely accessible models, the potential benefits of securitization and the leverage gained from leading in model capability development are much greater.

Today, open-source leaders like DeepSeek lag roughly half a year behind the frontier. If that gap widens, securitization means an even greater advantage over rivals. It means even more leverage over middle powers that need privileged access to models or the next-best open-source model. But if the gap narrows, securitization might make less sense; if the securitized frontier is quickly replicated and made accessible, then keeping a model under wraps does not do much.

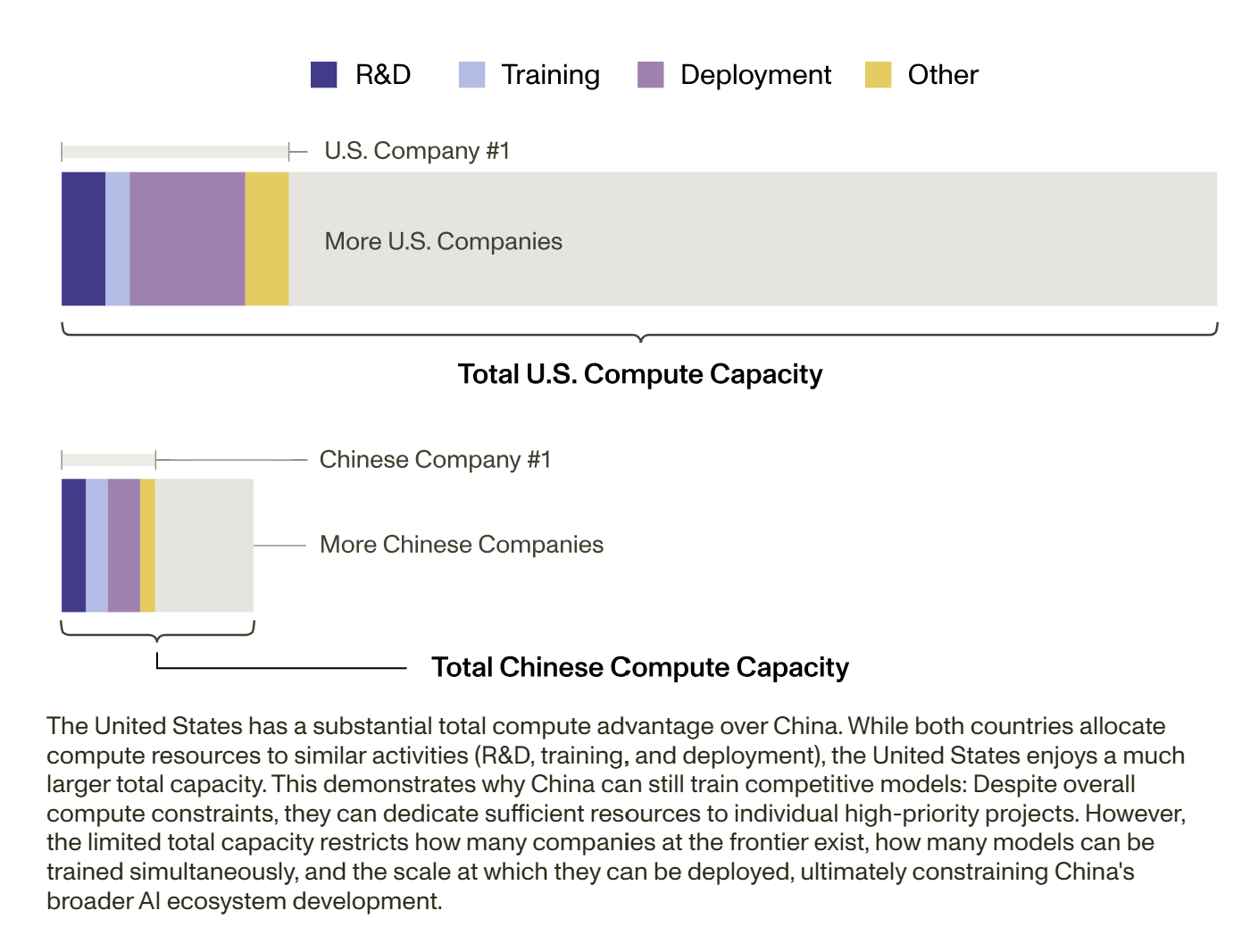

Current trends point in both directions: on one hand, the performance of Chinese-built and open-source models is catching up to US models. On the other hand, most capability progress is now driven by sophisticated agent systems, progress on which remains dominated by US developers, and on which China might be particularly hamstrung by enduring compute bottlenecks.

A corollary consideration here is the susceptibility of frontier models to misuse. If the proliferation of frontier AI leads to prohibitively harmful misuse, then even China could be forced to cut back on open-sourcing fast-follower models, in effect extending the gap between the frontier and widely available models.

3. Compute supply trends

It will matter whether US-controlled GPUs continue to remain a scarce and essential resource. They might become less essential if inference costs dropped further and if sufficiently strong models were widely available. They might become less scarce if Chinese suppliers rose to competitive levels, or if alternative technologies (e.g., Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), Amazon’s Trainium chips, or even alternative hardware solutions) took pressure off the Nvidia GPU market.

Again, trend lines point both ways. On one hand, between Huawei’s Ascend 910Cs and AWS’s 400,000 Trainium-2 devices, this year’s non-Nvidia chip buildout already makes for nearly one-tenth of 2024’s net growth in AI chips, reducing some tension in the blended-GPU supply curve. But, at the frontier, Nvidia still remains uncontested, signaling enduring supply shortages with no major relief expected throughout 2026.

While near-future relief seems unlikely, strategic postures usually take aim at longer time horizons. In a future where compute is relatively ubiquitous and abundant, it becomes much harder to pinch compute supply through straightforward export controls. In that world, great powers might need to either give up on the notion of strong leverage or quickly find a durable edge elsewhere. To be sure, Nvidia GPUs will remain a vital part of tomorrow’s economy. But, to be a central vehicle of geopolitical leverage, they’d have to retain the decisive degree of dominance they have today.

We lack clarity on how any of these three variables will play out. They are open, hotly debated questions in the field. Any strategy must be developed amid technical uncertainty, and any analysis of strategy must take place amid double uncertainty regarding technical possibilities and political motivations.

Many countries will have no say in AI’s impact. Where does all this disagreement and uncertainty leave the rest of the world? To begin with: in an unenviable position. If the export stances of great powers depend on big-ticket questions around strategy and technical paradigms, that leaves little room for most of the rest of the world to maneuver. Low-income countries seem set to have particularly little leverage; even the shift in their workforce toward higher-skilled digital work may not prove advantageous, as AI is set to disrupt these sectors most decisively.

Middle powers will have (some) agency. AI middle powers are advanced economies with some pathway toward a niche or lever in a world dominated by great AI powers. As a shorthand, perhaps consider the G20 save China and the US. How these middle powers react can also reflect and reshape the superpowers’ calculations, because a grand strategy might suffer if it pushes key partners into the rival’s camp or leaves them unwilling to adopt the leader’s rules.

So, what playbooks can middle powers use to find their place amid possible permutations of the two great powers’ strategies?

1. Securitized world

If Washington and Beijing lock their frontier models behind export fences and share leading compute and capabilities with a trusted circle of partners, middle powers must pick a patron to stay in the game. Their entry pass is to become both strategically indispensable and demonstrably trustworthy — much like Five Eyes members or nuclear NATO allies, which receive sensitive technology under tight safeguards. That means embedding themselves so deeply in a superpower’s supply chains or alliance architecture that cutting them off would be prohibitively costly. It also means showing that they can police leaks by running hardened data centers, enforcing export-control laws, and guarding model weights. Countries that fail to offer both leverage and security may risk slipping through the cracks, stuck with yesterday’s tools while the frontier speeds ahead.

2. Mercantilist world

In a world in which AI functions more like oil than weaponry, great powers exert influence by developing and selling — or withholding — the most valuable models and chips. In this setting, a middle power just needs a good source of revenue to participate in AI benefits and secure AI capabilities at home. An enduring revenue source might be achieved by providing useful data or natural resources, finding a niche in comparatively advantageous AI deployment, having a place in the AI supply chain, or creating AI-driven revenue somewhere down the value chain (e.g., in manufacturing). The essential element is that a middle power partakes to some extent in AI-driven growth; as long as it does that, it can afford to buy chips and model access to remain stable and prosperous.

Middle powers with this kind of niche could even be tempted to balance between the great powers, trying to make favorable deals where possible. This strategic stance is perhaps not unlike India’s, in recent years, often aiming to retain somewhat amicable relations with China and a strong economic integration with the US and its major technology corporations. In many ways, a mutually mercantilist environment like this lends itself to a fairly equitable distribution of AI capabilities; it might be the least volatile and the most stable.

3. World of clashing doctrines

In a world of differing great-power strategies, middle powers face the most difficult challenge. If the US retains an enduring edge in frontier models (whether through talent or compute), and if China continues to lag roughly six months behind, the incentives might shake out as follows: the US wants China not to close the gap, so that the US reaches decisive strategic points in the development of very advanced systems earlier and maintains a general lead in security-forward adoption. Accordingly, the US securitizes. China recognizes that it cannot readily close the gap, and bets on a different technical trajectory instead: it tries to play for an advantage on different grounds, especially economic and diplomatic, by generating valuable alliances and revenue through a highly liberal diffusion regime, perhaps including open-source technology. As a side effect, China undercuts the US AI market share by offering dramatically lower (perhaps subsidized) prices and better conditions.

In such a scenario, middle powers’ incentives become more difficult still: they must decide whether to aim for alignment with the US (ensuring a costly place at the frontier) or to settle for cheaper alignment with China. Choosing wrong can quickly go awry (for example, if securitized capabilities suddenly become important to competitiveness or security, after a middle power has already foregone US alignment).

Whether winning the AI race ultimately means securing military dominance, economic primacy, or spheres of influence, middle powers will have to make choices that interface with the strategies of the US and China. They can find niches and comparative advantages. They can look for parts of their economy to boost through deploying AI effectively. They can look to leverage idiosyncratic advantages like proprietary data, natural resources, or other important links within the broader AI supply chain.

Each of these strategies, however, is contingent on access to compute, to model weights, and to advanced AI systems and their APIs. Middle powers control none of these resources, so their access depends on the foreign and trade policies of great powers.

The implications of that fact cut both ways. They place a burden of responsibility on great powers; while seemingly determined to pursue AI supremacy, the US and China should consider their stake in the new geopolitical order that their decisions will shape. But, first and foremost, these findings should matter to middle powers: they should look much, much more closely at great powers’ diffusion stances than they have to date, examining what they might mean. The rest of the world disregards AI grand strategy at its own extraordinary peril.

The White House is betting that hardware sales will buy software loyalty — a strategy borrowed from 5G that misunderstands how AI actually works.

AI automation threatens to erode the “development ladder,” a foundational economic pathway that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.