Making Extreme AI Risk Tradeable

Traditional insurance can’t handle the extreme risks of frontier AI. Catastrophe bonds can cover the gap and compel labs to adopt tougher safety standards.

Last November, seven families filed lawsuits against frontier AI developers, accusing their chatbots of inducing psychosis and encouraging suicide. These cases — some of the earliest tests of companies’ legal liability for AI-related harms — raise questions about how to reduce risks while ensuring accountability and compensation, should those risks materialize.

One emerging proposal takes inspiration from an existing method for governing dangerous systems without relying on goodwill: liability insurance. Going beyond simply compensating for accidents, liability insurance also encourages safer behavior, by conditioning coverage on inspections and compliance with defined standards, and by pricing premiums in proportion to risk (as with liability policies covering boilers, buildings, and cars). In principle, the same market-based logic could be applied to frontier AI.

However, a major complication is the diverse range of hazards that AI presents. Conventional insurance systems may be sufficient to cover harms like copyright infringement, but future AI systems could also cause much more extreme harm. Imagine if an AI orchestrated a cyberattack that resulted in severe damage to the power grid, or breached security systems to steal sensitive information and install ransomware.

The market currently cannot provide liability insurance for extreme AI catastrophes. This is for two reasons. First, the process of underwriting, which involves assessing risk and setting insurance prices, requires a stable historical record of damages, which does not exist for a fast-moving, novel technology like AI. Second, the potential scale of harm caused in an AI catastrophe could exceed the capital of any single carrier and strain even the reinsurance sector.

In other words, conventional insurance covers frequent, largely independent events that result in a limited amount of harm. AI risks, meanwhile, are long-tailed. While most deployments will proceed without incident, rare failures could snowball into damages beyond the capacity of the insurance market to absorb.

Catastrophe bonds can fill the gap left by conventional insurance. As an alternative market-driven solution to liability insurance, we propose AI catastrophe bonds: a method of insurance tailored to cover a specific set of large-scale AI disasters, inspired by how the market insures against natural disasters. As well as offering coverage, our proposal would be structured to encourage higher safety standards, reducing the likelihood of all AI disasters.

A proven capital-markets model for tail risk already exists. AI may be a novel technology, but it is not the first phenomenon to present the challenge of rare, extremely harmful events. From hurricanes in Florida to earthquakes in Japan, natural disasters offer a precedent for dealing with such tail risks. In these cases, the insurance industry packages liabilities in the form of financial assets called insurance-linked securities (ILS). These can be sold to global capital markets, transferring specific insurance risks to the deepest pool of liquidity in the world. Investors receive attractive returns in exchange for bearing potential losses from designated catastrophic events.

The most notable example of ILS are catastrophe (cat) bonds. Typically covering natural disasters and cyberattacks, cat bonds are designed to offload extreme risks that conventional insurers struggle to hold. A reinsurer sponsors a bond that pays a high yield but automatically absorbs losses in the event of a predefined disaster. In effect, capital markets become the backstop for extreme events.

Natural buyers of cat bonds include hedge funds, ILS funds, and other institutional investors: they have both the sophistication to price complex, low-probability risks and the appetite for asymmetrical, nonlinear payoffs. In return for accepting the risk of total loss, they receive outsized yields.

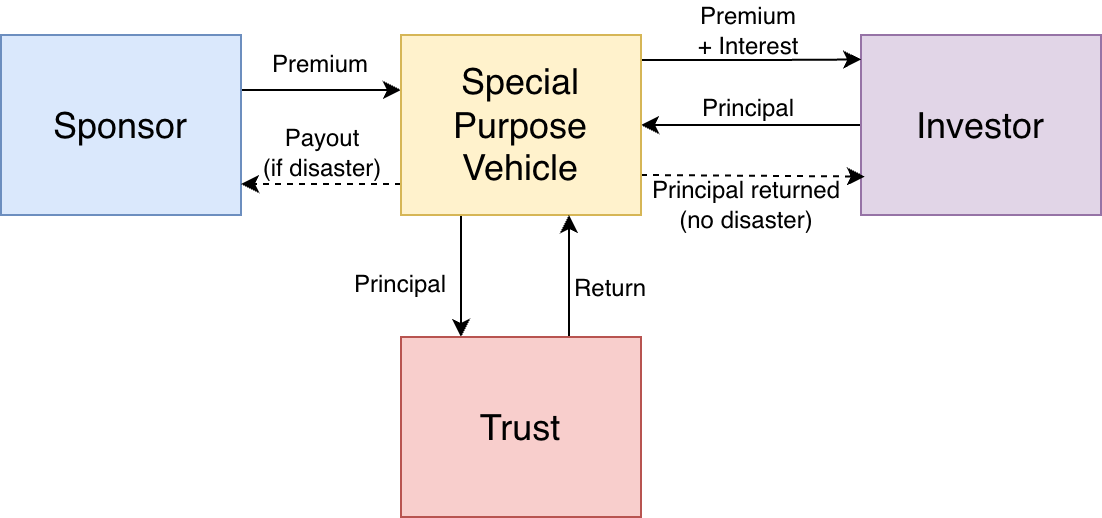

Here’s how cat bond money flows among stakeholders:

Taking this mechanism as a blueprint for AI, frontier developers could similarly sponsor “AI catastrophe bonds,” transferring the tail risk to a pool of capital-market investors, who would accept it in exchange for high yield.

/inline-pitch-cta

/inline-pitch-cta

Catastrophe bonds can benefit AI developers. Although AI developers are not currently automatically liable for all AI-related harms, they could nonetheless stand to benefit from issuing cat bonds. Several developers are already facing lawsuits, such as those described earlier, alleging that their products have caused mental illness and wrongful death. Given the long tail of potential dangers, companies may prefer to obtain protection from major losses, even if the harms for which they may bear liability have not yet been extensively tested in court.

Regulations could make coverage mandatory. Beyond AI developers’ own motivations, regulators could also mandate that frontier developers maintain minimum catastrophe bond coverage as a licensing condition, similar to liability requirements for nuclear facilities or offshore drilling.

In technical terms, an AI developer would issue a cat bond through a type of legal entity called a special purpose vehicle (SPV). When investors purchase the bond, their funds are held as collateral inside the SPV (typically in safe, liquid assets). In normal times, the developer pays investors a “coupon,” which is economically analogous to an insurance premium. If a defined AI “catastrophe” trigger occurs (more on that below), some or all of the collateral is released to fund payouts, and investors absorb the loss.

Investors could buy AI cat bonds as part of a hedged strategy. It is worth noting one important difference between AI risks and the types of risks traditionally covered with cat bonds: correlation with market performance. Natural disasters are largely uncorrelated with the financial markets, making the cat bonds covering them more appealing to investors. On the other hand, an AI-related event severe enough to trigger a payout would probably prompt a sharp repricing of AI equities.

This effect means any losses would likely occur at a particularly bad time for investors, which might reduce appetite for AI cat bonds specifically. Yet it also opens the door to hedged strategies, such as earning interest from AI cat bonds while betting against tech stocks. In this sense, AI cat bonds would make the tail risk of AI tradeable for the first time.

Cat bonds can incentivize safety, not just transfer risk. As well as helping to cover damage from catastrophes, it is equally if not more important that AI cat bonds reduce the likelihood of such events happening in the first place. As with regular insurance, the bonds therefore need to financially incentivize rigorous safety standards. This could be done by setting each developer’s coupon at a base rate plus a floating surcharge that reflects that developer’s safety practices.

A Catastrophic Risk Index would tie pricing to standardized safety assessments. For this to work, there would need to be a standardized, independent assessment of AI developers’ safety posture and operational controls, which we’ll call a Catastrophic Risk Index (CRI). Like credit ratings in debt markets, the CRI would translate safety practices into a transparent cost of capital. Safer labs pay less and riskier labs pay more, directly aligning incentives to reduce risk.

Consider this visualization of AI cat bonds’ potential structure:

The building blocks for a credible CRI are already emerging. Constructing a credible CRI is not a trivial undertaking, but the necessary infrastructure is already emerging. Dedicated AI safety organizations — such as METR, Apollo Research, and the UK AI Safety Institute — have developed evaluation frameworks for dangerous capabilities and alignment robustness. Meanwhile, bodies like the AI Verification & Evaluation Research Institute (AVERI) are being set up specifically to advance frontier AI auditing. An industry consortium or standards authority could consolidate these inputs into a unified, transparent index.

This would bring yet another safety benefit: for AI cat bonds to be investable, frontier developers would need to publicly disclose technical and operational risk metrics and submit to third-party audits. This transparency is a feature, not a drawback: it would provide the inputs necessary for the CRI, allowing capital markets to form independent price views rather than relying on guesswork.

/odw-inline-subscribe-cta

The market for AI cat bonds could start small and develop alongside safety evaluations. Initially, while CRI methodologies mature, the first AI cat bonds would be modest and bespoke. But, as the index gains credibility, and as trigger mechanisms for payouts prove robust, the market could scale rapidly. The most convincing demonstrations of trigger robustness would be actual incidents that test the legal system's capacity to assign responsibility and cat bonds’ ability to pay out fairly and efficiently. Yet, in the absence of such incidents, market confidence could still develop through rigorous third-party oversight, independent auditing of the trigger criteria, and broader institutional trust in leading AI developers.

/odw-inline-subscribe-cta

As a knock-on effect, market confidence could catalyze secondary insurance and reinsurance markets. Traditional reinsurers that are currently unable to warehouse AI tail risk would gain a hedging and price-discovery tool through the AI cat bonds. Simultaneously, these bonds would offer investors a new form of insurance-linked security and a direct way to express a view on AI risk. The CRI would provide a basis for relative-value analysis: investors could compare risk-adjusted yields across companies, rewarding safer operators with lower premiums.

In practice, AI cat bonds will require precise specification of when payouts should happen. Existing cat bonds have a range of “trigger mechanisms,” each with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Payout triggers could be court decisions, measurable events, or industry-wide claim thresholds. One tradeoff is between the speed of payouts and their accuracy. For instance, a trigger mechanism based on court-awarded damages is likely to be accurate but slow, leaving victims uncompensated while investors endure prolonged uncertainty. On the other hand, parametric triggers, which are based on objectively measurable events (for example, an AI autonomously gaining access to resources above a certain threshold), would enable faster payouts, but present the challenge of specifying which measurable events reliably indicate catastrophe.

A third option is an “index-based” trigger mechanism, which would release payouts when total AI-attributed losses surpass a specified level across the whole industry. This avoids company-specific attribution disputes, but it could weaken safety incentives by sharing the costs of failures across developers, potentially diluting the consequences of inadequate safety standards for any individual developer. CRI-linked premiums as described above could help to mitigate this effect, however.

Market experimentation will determine which triggers work best. The most practical near-term design may combine elements of these trigger mechanisms to balance their advantages and disadvantages. For example, a parametric trigger might place funds in escrow upon detection of specified technical failures, with final disbursement happening after court confirmation of liability. Early AI cat bonds will likely experiment with multiple structures, and market selection will determine which designs are most effective.

AI cat bonds should give investors high returns due to uncertainty about loss events. To attract investors, the entities issuing cat bonds typically pay an annual coupon several times larger than the annual expected loss as a percentage of investors’ funds. The coupon is calculated as a base rate of the annual expected loss, plus that expected loss multiplied by a number called a “risk multiple.” Historical catastrophe bond data from Artemis suggests risk multiples of roughly 2–5, with higher multiples for novel or poorly modelled risks.

For AI catastrophes, the true probability of a covered loss event is highly uncertain. We estimate an annual expected loss of 2% of the funds in the SPV and a risk multiple of 4–6. The developer’s annual payment would then be 2% + (4–6)*2% = 10%–14% of the funds invested in the SPV. This pricing would be broadly consistent with historical ILS treatment of novel, high-uncertainty risks.

The AI industry could plausibly support an initial collateral of up to $500 million. From the above chart, we can estimate the initial market size. Frontier AI labs already spend hundreds of millions annually on safety research and compliance, so it is not implausible that they might assume an insurance premium of ~$10 million. If five major labs were to participate (for instance, Google DeepMind, OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, and xAI), aggregate annual premiums would total approximately $50 million. If this amount represents 10%–14% of the funds invested into the SPV, this would support a collateral of $350 million to $500 million available to draw from in the event of a covered catastrophe. This estimate is comparable to mid-sized natural-catastrophe bonds, but it represents a floor; regulatory mandates, broader industry participation, and growing investor confidence could, within years, expand the market to $3 billion and $5 billion.

If investors showed a lack of demand, this would itself be informative: bonds failing to sell at plausible prices would signal that the underlying risk of an AI catastrophe may be higher than developers or regulators have assumed.

In summary, we propose AI catastrophe bonds: a way for frontier AI developers to buy protection against extreme, low-probability harms without engaging the insurance industry. Frontier AI risks are largely uninsurable through conventional channels: insurers lack the historical data to price policies and face risk profiles that don't fit their risk appetite. Capital markets investors (like ILS funds and hedge funds), however, are well-suited to taking the other side of such bets, much as they already do for earthquake and hurricane risks. Meanwhile, several AI safety organizations are already developing credible risk-evaluation methods, which are necessary to continually inform and update the premiums that AI companies pay.

AI catastrophe bonds would benefit developers, investors, and society. This variable pricing is the key: each developer’s premium rises or falls with an independent index based on audited safety and governance metrics of that developer. Such a framework would create strong financial incentives to improve safety standards, reducing the likelihood not only of catastrophes covered by the bonds but also of worst-case, extinction-level scenarios. This is a win-win-win: labs get coverage, investors get a handsome risk premium, and society gets a market-driven safety mechanism.

See things differently? AI Frontiers welcomes expert insights, thoughtful critiques, and fresh perspectives. Send us your pitch.

See things differently? AI Frontiers welcomes expert insights, thoughtful critiques, and fresh perspectives. Send us your pitch.

The White House is betting that hardware sales will buy software loyalty — a strategy borrowed from 5G that misunderstands how AI actually works.

AI automation threatens to erode the “development ladder,” a foundational economic pathway that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.