Exporting Advanced Chips Is Good for Nvidia, Not the US

The White House is betting that hardware sales will buy software loyalty — a strategy borrowed from 5G that misunderstands how AI actually works.

Last week, the US government gave chip-maker Nvidia the green light to sell its H200 graphics processing units (GPUs) to approved buyers in China. These GPUs were previously subject to export controls preventing their sale to China. Following Nvidia’s record-breaking $5 trillion valuation, in October, this approval squares neatly with the views of many US policymakers who argue for an AI strategy focused on exporting US technology at scale. Among them is Sriram Krishnan, senior White House policy advisor on AI, who has stated the economic motivations bluntly: “Winning the AI race = market share.” Krishnan’s approach contrasts starkly with that of the Biden administration, which aimed to defend American AI leadership and protect against national security threats through increasingly stringent restrictions on exports of US AI hardware.

The White House’s July 2025 AI Action Plan, which lays out its export-focused strategy in depth, argues that selling the “full AI technology stack — hardware, models, software, applications, and standards” is the key to preventing other countries from adopting rivals’ solutions instead. The US could thus entrench its position as the leading provider of AI, the rationale goes, and secure long-term influence over not only AI hardware but also the AI models and applications used around the world.

In practice, much of the focus has been on exports of AI hardware, given strong global demand for Nvidia GPUs. However, a strategy that emphasizes AI chip exports as the path to US leadership will likely fail to translate into a lasting competitive advantage across the AI stack. It is not safe to assume that increased market share at one layer of the stack automatically promotes market share in other layers — if anything, the opposite sometimes proves true. Diffusion of America’s most advanced AI technology to the rest of the world could also weaken US national security if poorly managed. Meanwhile, there are smarter, more structured approaches to offering other countries access to American AI. Renting chips in US-based data centers, for example, could bring the US many of the same — or even more — economic benefits, while mitigating risks effectively.

Ramping up chip exports would increase Nvidia’s market share in China, but, as far as the wider US AI ecosystem is concerned, the advantages might end there. In fact, selling chips will likely increase competition for US companies at the model and application layers, because there is nothing to stop customers with US chips from training or running non-US models on them. Selling more hardware may therefore mean that AI developers based in China and elsewhere have more resources to develop competing models. Meanwhile, US AI companies have faced shortages of AI chips and are competing for supplies of these with companies outside the US. Therefore, increased AI hardware exports could also weaken the ability of US companies to accumulate enough AI chips to train models at the frontier of technology.

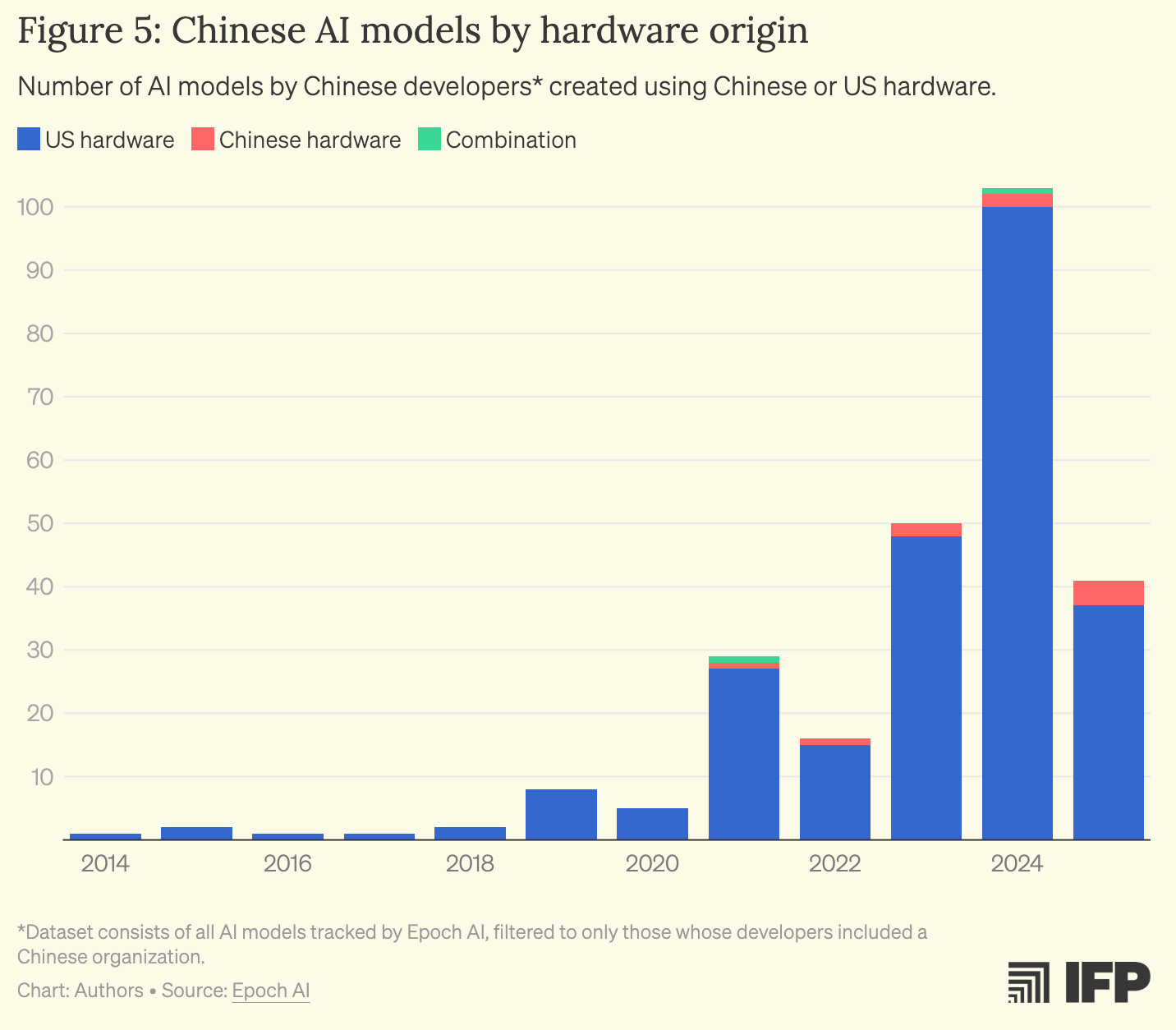

US chips are already being used to train and run the vast majority of non-US models. Last year, out of 103 AI models created by Chinese AI developers, 100 were trained on US hardware. Nvidia is the largest supplier of AI chips to China, where they are primarily used to train and run Chinese models, demonstrating how access to American hardware is accelerating the growth of China’s AI industry. Additionally, even exporting chips to other countries outside China might indirectly give Chinese AI developers more resources to train their models.

This is in part due to chip smuggling, enabled by poor enforcement of export controls; reports suggest that American AI chips smuggled to China in 2024 numbered in the tens to hundreds of thousands. Yet, even if GPUs stay in the countries that imported them, those countries may end up renting them out — especially if they do not have a well-developed strategy for how to use them domestically — and the largest non-American customers would likely be Chinese AI developers. This is already happening on a large scale in Malaysia and other countries in Southeast Asia, where Chinese developers such as ByteDance and Alibaba are accessing large volumes of US chips.

More availability of chips outside the US currently favors Chinese models, not US ones. Rather than putting all developers on an even footing, greater availability of AI chips might actually promote the use of non-US models above those from the US. This is because many enterprise or government users may prefer to run open-source models — which give them better privacy and customizability — and the majority of the most capable open-source models are Chinese. An early indication of this possibility came in September, when the open-source model family Qwen, developed by Alibaba, overtook Meta’s Llama models as the most popular open-source model in the world. Many users of open-source Chinese models are Western companies running them on American chips.

The drive to export is based on learning the wrong lessons from past China-US competition. Given that the widespread proliferation of US chips does not necessarily create broader dependence on American models and applications, why are many policymakers convinced that it does? One explanation may be that policy-makers are fighting the last war and trying to learn lessons from previous Chinese successes in technology competition, such as Huawei’s exports of 5G infrastructure. Michael Kratsios, who directs the White House Office for Science and Technology Policy, has drawn this analogy, noting, in an interview with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, that other countries “didn’t want to buy [Western alternatives to Huawei telecommunications systems] because the U.S. just was not able to create the environment and the packages necessary to export it out.” Advocates of an export-led strategy argue that the US cannot allow the same to happen with AI.

/inline-pitch-cta

Yet this comparison does not stand up to scrutiny. In 5G, hardware and software are tightly integrated; if a country has Huawei 5G equipment, it must use Huawei 5G software as well. AI chips, on the other hand, are designed as general-purpose hardware for training and running a wide range of models. Once the GPUs are sold, US companies have no control over what customers use them for and cannot ensure any continuing returns at other layers of the AI technology stack.

Pro-export policymakers have acknowledged these issues. In fact, Dean Ball, primary staff author of Executive Order 14320, “Promoting the Export of the American AI Technology Stack,” has recognized this problem himself. Writing last month about what the EO was trying to achieve, Ball acknowledged: “We could end up constructing data centers abroad—and even using taxpayer dollars to subsidize that construction through development finance loans—only to find that the infrastructure is being used to run models from China or elsewhere.”

To avoid this outcome, he suggests that American AI model developers could, with government support, work with US hardware providers and data center operators to build infrastructure and run AI services in other countries. Ball points out that some developers are already starting to pursue a strategy of this kind. “OpenAI for Countries,” for example, seeks to build data centers abroad and to offer versions of ChatGPT tailored to local needs, while protecting democratic principles and continuing to improve safety standards.

By providing comprehensive solutions and ongoing support, partnerships like this could promote US market share in AI models over the longer term, helping to address concerns around security and lasting economic returns. But in practice, most sales currently being made are not within this framework. The deals announced so far have predominantly been straightforward exports of hardware, often without any publicly announced conditions to address the issues mentioned above.

Even if selling US chips would not boost the use of American models around the world, some may argue that the US must export hardware anyway, to defend market share at the hardware layer. David Sacks, who chairs the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, recently voiced this anxiety, posting on X: “China is exporting Huawei chips + DeepSeek models to the Global South. If we don’t make it just as easy to export the American AI stack, we will forfeit this technology race in large parts of the world.” Yet current evidence suggests that Sacks’s concern is unfounded in the near term.

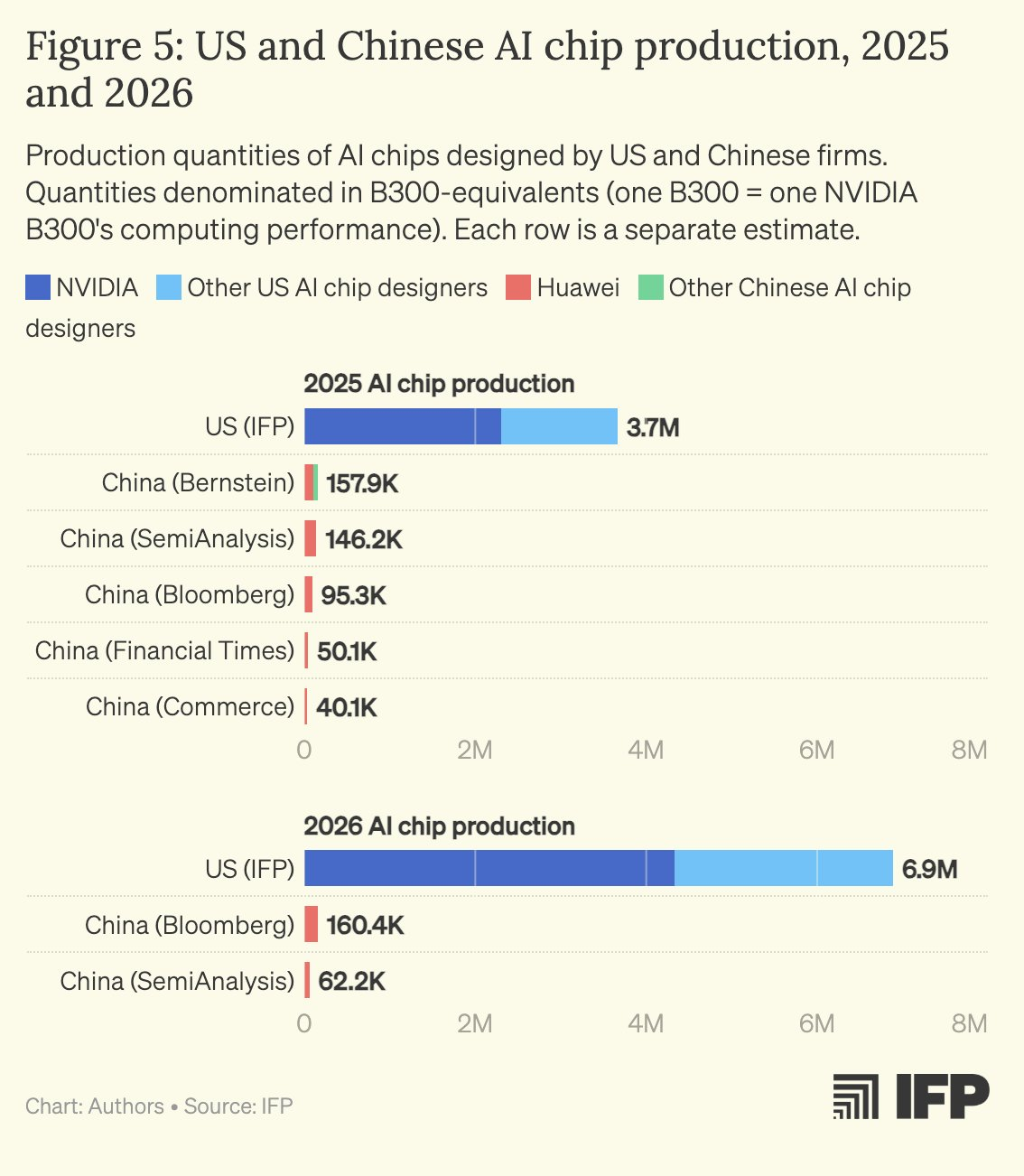

China is not producing enough AI chips to meet its domestic demand, let alone for export. Production of Huawei’s Ascend AI chips — estimated at 805,000 units this year — still falls far short of China’s domestic demand, which continues to be met in large part by Nvidia. Huawei is not exporting AI chips yet, and it is unlikely to do so before it can satisfy hardware needs within China. Industry analysts forecast that unless Huawei, China’s largest AI chip manufacturer, can secure new imports of High Bandwidth Memory (HBM), which is currently subject to US export controls, its production of AI chips will actually fall next year.

Chinese AI chips will likely not match the performance of American chips for several years. Even according to Huawei’s own announced roadmap, it will not produce a chip that can compete with the Nvidia H200 on performance until Q4 2027 at the earliest. In addition, Chinese AI chips suffer from issues with lower reliability, primarily due to a software ecosystem that is less mature and well-developed than Nvidia’s Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA). This makes it significantly more expensive and time-consuming to train AI models using Chinese chips relative to Nvidia’s.

Exports of AI chips are unlikely to guarantee long-term US dominance across all parts of the AI industry. They also carry real national security risks that need to be considered alongside the economic impacts.

/odw-inline-subscribe-cta

Exporting chips could enable adversaries to train models that pose a threat to the US. AI models are generally a dual-use technology, with civilian uses as well as military applications (including command and control, autonomous weapons systems, and cyberattacks). Exporting GPUs en masse could significantly expand the pool of actors with the necessary resources to train and run powerful, hazardous models — the kind top frontier labs typically keep walled off until after they have established proper guardrails. As highlighted above, the US will have no control over how its chips are used once they are exported. Selling them in large numbers, particularly beyond close allies, could therefore pose a serious national security threat to the US.

This risk is not unknown to pro-export policy-makers. Indeed, in April this year, it was part of the motivation for introducing stricter controls on exports of Nvidia’s H20 chips to China. In relation to that policy, Krishnan noted: “When it comes to inside China, I do think there is still bipartisan and broad concern about what can happen to these GPUs once they are physically inside.” Yet in the months since then, this concern seems to have been pushed aside, as the White House first reversed the restrictions on the H20, and then announced it would allow sales of an even more powerful chip — Nvidia’s H200 — to China as well. Moreover, with Nvidia’s advanced Blackwell GPUs being exported to other countries, there seems to be little acknowledgement that actors outside China could also use the chips in ways that threaten the US.

Adversaries with access to the weights of US models could bypass guardrails. Supporters of an export-focused AI policy might argue that this is why the US needs to export the full stack; by providing access to US models alongside the hardware, America could ensure that the default models in use reflect Western values and have guardrails in place to prevent their deployment in foreign military applications, for example. Yet, unless this is done under a carefully considered framework in which developers retain ongoing oversight, as Ball suggests, simply offering American models would do little to mitigate the risk; with sufficient hardware and access to a model’s weights, customers could retrain it to circumvent any intended limitations on its use. Today, this risk is largely theoretical, since most of the leading open-source models come from China. But if America were to regain the lead in developing open-source models and then export these to the world, providing access to a sophisticated model, even one with guardrails, could expedite adversaries’ activities, since retraining the existing model might be easier than trying to train a powerful new model from scratch.

Rather than maximizing exports at all layers of the AI technology stack, the US should develop a more nuanced strategy that balances economic goals with security concerns.

Fortunately, the US need not choose between the goals of capturing the benefits of global demand for American AI chips, retaining leadership in other parts of the AI stack, and protecting US national security. Multiple alternatives to one-time GPU sales achieve a more attractive balance between these priorities. Ball’s proposed framework could work well for some countries, but there is no one-size-fits-all solution. For example, in cases where nations want more freedom around which models they use, another approach would be to rent access to US-based hardware. The degree of model control and customization would depend on a country’s objectives for the rental and their alignment with US safety and security standards.

Renting chips could be more economically beneficial than selling them. Instead of selling large quantities of AI hardware, the US could focus on providing greater cloud access to chips hosted in data centers within the US or closely allied countries, as Janet Egan and Lennart Heim have proposed. For American companies, this strategy would have many of the same economic benefits as selling chips. In fact, it could be even more advantageous, providing a continuous revenue stream over the long term rather than one-off sales.

US cloud providers could vet users of AI chips. Unlike selling chips, however, renting them would grant the US meaningful oversight and control of how they are used. This makes it a far better proposal in terms of national security. At the user level, providers could implement know-your-customer requirements to prevent their compute being accessed by adversaries. This would also allow the US government to impose restrictions on which countries could access the GPUs by, for example, preventing China from renting them. This stands in contrast with exporting hardware, which gives companies no control over, or even knowledge of, where their chips end up or by whom they’re used, as chips can easily be resold or smuggled.

US cloud providers could detect and prevent prohibited activities. As well as vetting customers, US-based cloud providers could also monitor how chips in their data centers are being used, identifying and preventing prohibited activities (such as large training runs that could produce models at the frontier of capabilities, which could pose heightened risks and require extra guardrails). Additionally, customers could use American models without getting access to their weights, meaning they would not be able to retrain them to remove safeguards.

Hardware-only sales undermine the security advantages of deals that offer more control. Whether a country would opt to rent US-based chips or to have its own infrastructure built locally through an “OpenAI for Countries”–style partnership would depend on its priorities. Those seeking more freedom to use open-source models, for example, would prefer the former, while those wishing to avoid dependence on data centers abroad would choose the latter. But the security advantages of either solution will be undermined if the US continues to pursue large volumes of hardware-only sales as well.

If the drive to export as much as possible leads to large chip sales with no strings attached, similar to those made in recent months, it will amplify the national security risks of AI while failing to guarantee long-term predominance of American technology or lasting advantages for the US AI industry. America can make much better use of its technological lead, either by exporting in a carefully structured way or by renting access to US-based hardware. Reaping the economic benefits of AI does not require compromising US security.

See things differently? AI Frontiers welcomes expert insights, thoughtful critiques, and fresh perspectives. Send us your pitch.

Traditional insurance can’t handle the extreme risks of frontier AI. Catastrophe bonds can cover the gap and compel labs to adopt tougher safety standards.

AI automation threatens to erode the “development ladder,” a foundational economic pathway that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.