AI Could Undermine Emerging Economies

AI automation threatens to erode the “development ladder,” a foundational economic pathway that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.

Earlier this year, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei warned that powerful AI could render upwards of 50% of white-collar jobs redundant, with the impact concentrated on entry-level jobs. If these predictions hold true, it could imply a long-term crisis of skill acquisition. Without the training ground of a first job, young workers could be denied the experiences and networks necessary to enter white-collar work. Their career trajectories could be severed before they begin.

AI is likely to disrupt more than the professional trajectories of individuals. The threat to career development mirrors a broader geoeconomic threat AI poses to developing countries: just as young workers need entry-level roles to climb into more senior roles, developing nations need viable “entry-level” industries to develop their human capital and ascend the global economic development ladder.

Many economies have followed a similar path for development over the past several decades. The most reproducible strategy has traced a familiar sequence: moving from low-skill agrarian production, to building a globally competitive manufacturing base, and eventually to exporting higher-value services and technology.

Such a progression is often described as a development ladder — a series of rungs that countries climb as they accumulate the capital and capabilities to compete in the global marketplace. This ladder is at risk from the coming wave of AI-driven automation.

South Korea is a canonical example of a successful development ladder. In 1953, its GDP per capita was $67 — among the lowest in the world, with little infrastructure and no natural resources. To bring the country out of poverty, President Park Chung-hee’s government made a bet on competitive manufacturing. Korea would compete globally, starting with the simplest products.

Over the next 50 years, Korea built entirely new industries from scratch: steel mills without any iron, petroleum refineries despite importing all oil. Textile manufacturing in the 1960s led to heavy industry in the 1970s, which spurred the development of an electronics industry in the 1980s. By 2020, South Korea’s GDP per capita reached $33,000: a nearly 500-fold increase in just 70 years.

Though Korea had other critically necessary benefits, such as strong pro-capitalist economic institutions and strategic American support, its ascent depended on a long window of successful export growth. At the heart of this success was labor arbitrage: Korean workers could produce goods at a fraction of the labor cost in developed economies, making Korean exports highly competitive.

Labor arbitrage has been the key enabler of export-driven development. There are dozens of determinants for the success of countries leveraging the export-led development ladder. Crucial requirements have historically included strong political and economic institutions, effective education systems, and access to major waterways. Developing countries benefit in comparison to their developed counterparts from reduced land costs, minimal regulatory burdens, and occasionally, generous tax incentives. However, perhaps their strongest driver has been wage competitiveness.

Export-driven development ladders are optimized around abundant and relatively inexpensive human labor. A garment worker in a developing country earning $3 a day, competing against an American earning $150, creates a 50:1 wage differential that makes this comparative advantage inevitable. This holds true even after accounting for shipping costs, quality variance, and supply chain complexities.

In many ways, this system is mutually beneficial for both producers and consumers. Consumers in wealthy countries receive access to cheaper goods. Developing countries gain capital investment and access to global markets, but also something far more valuable: systematic capability-building.

Labor arbitrage unlocks subsequent rungs on the development ladder. Through what development economists call “learning-by-doing” spillovers, foreign investment also inadvertently transfers technology and know-how that can eventually transform developing economies. The low-paid workers assembling electronics learn precision manufacturing, supervisors learn quality control systems, and so on. These workers eventually leave — starting businesses, joining competitors, or training others — and over time, dispersing skills throughout the economy.

Exemplified by East Asian states such as South Korea, Japan, China, and Taiwan, countries prioritizing export-driven manufacturing strategies have lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty since the 1960s. Large-scale manufacturing has succeeded by transferring capital, technology, and learning-by-doing to massive, previously unskilled labor forces over decades.

Today, countries such as India, Vietnam, and Bangladesh are betting on growing manufacturing industries to continue their development. However, they are also facing headwinds: the past two decades have displayed persistent trends of premature deindustrialization, in which modern countries are running out of industrialization opportunities sooner and at much lower levels of income compared to earlier developing countries.

Digital services have been emerging as an alternative to manufacturing. More recently, attention has shifted in many developing nations towards exporting digital services. Contemporary developing countries, especially those in Sub-Saharan Africa, have explicitly positioned themselves around fintech, business process outsourcing (BPO), and information technology (IT) rather than attempting to replicate East Asia’s manufacturing-led model.

/inline-pitch-cta

This is seemingly a rational response for the 21st century: why invest decades in building labor-intensive manufacturing when you can leverage educated populations, mobile connectivity, and English proficiency? By working remotely for companies in the developed world, locals in developing economies earn 2-4 times higher wages than manufacturing, and in better working conditions. Through this approach, many developing countries hope to leapfrog directly from agriculture to knowledge work.

Transformative AI (TAI) systems, defined as systems that precipitate a transition comparable to the agricultural or industrial revolution, could fundamentally break this equation by reducing opportunities for global labor arbitrage across the board. If AI systems can function as “drop-in remote workers” — by the end of the 2020s, according to Amodei and other experts — they would likely do so at a much cheaper cost than humans working from developing countries. This could strip away several early rungs of the export-driven development ladder.

In this future, digital services could face rapid automation, with value moving from contractors in developing countries to AI systems operated by corporations in wealthy nations. Simultaneously, AI-driven automation could lead to increasingly capital-intensive manufacturing processes, pricing out countries that cannot afford expensive automation. Together, these dynamics could close the primary pathways available to late developers.

This could happen in three specific ways:

The obvious irony of this latest wave of AI automation is that digital services are being automated faster and more completely than manual labor — precisely when many developing countries were betting on them as their primary development pathway.

Africa offers several excellent examples. Kenya is launching a national business process outsourcing (BPO) policy seeking to bring in a million jobs over five years, and has been pouring resources into call centers, content moderation, and data labeling. In 2013, Rwanda launched a plan to become the “Singapore of Africa,” prioritizing the build-out of its internet infrastructure to attract foreign firms for remote digital employment.

Unfortunately, the strategy of leapfrogging via digital arbitrage appeared most promising before the release of ChatGPT. Today, those countries are beginning to discover that the digital services pathway could be closing even faster than manufacturing. Many forms of digital services could be automated within a few years of developing powerful AI systems because of near-zero marginal costs — deployment costs essentially nothing beyond API calls.

Call centers are a backbone of digital services arbitrage, yet chatbots could automate much of the industry over the next decade. Business process outsourcing — data entry, invoice handling, claims processing — is expected to see a loss of perhaps half a million jobs in India over the next three years. Even services such as content moderation and data annotation are at risk from AI automation.

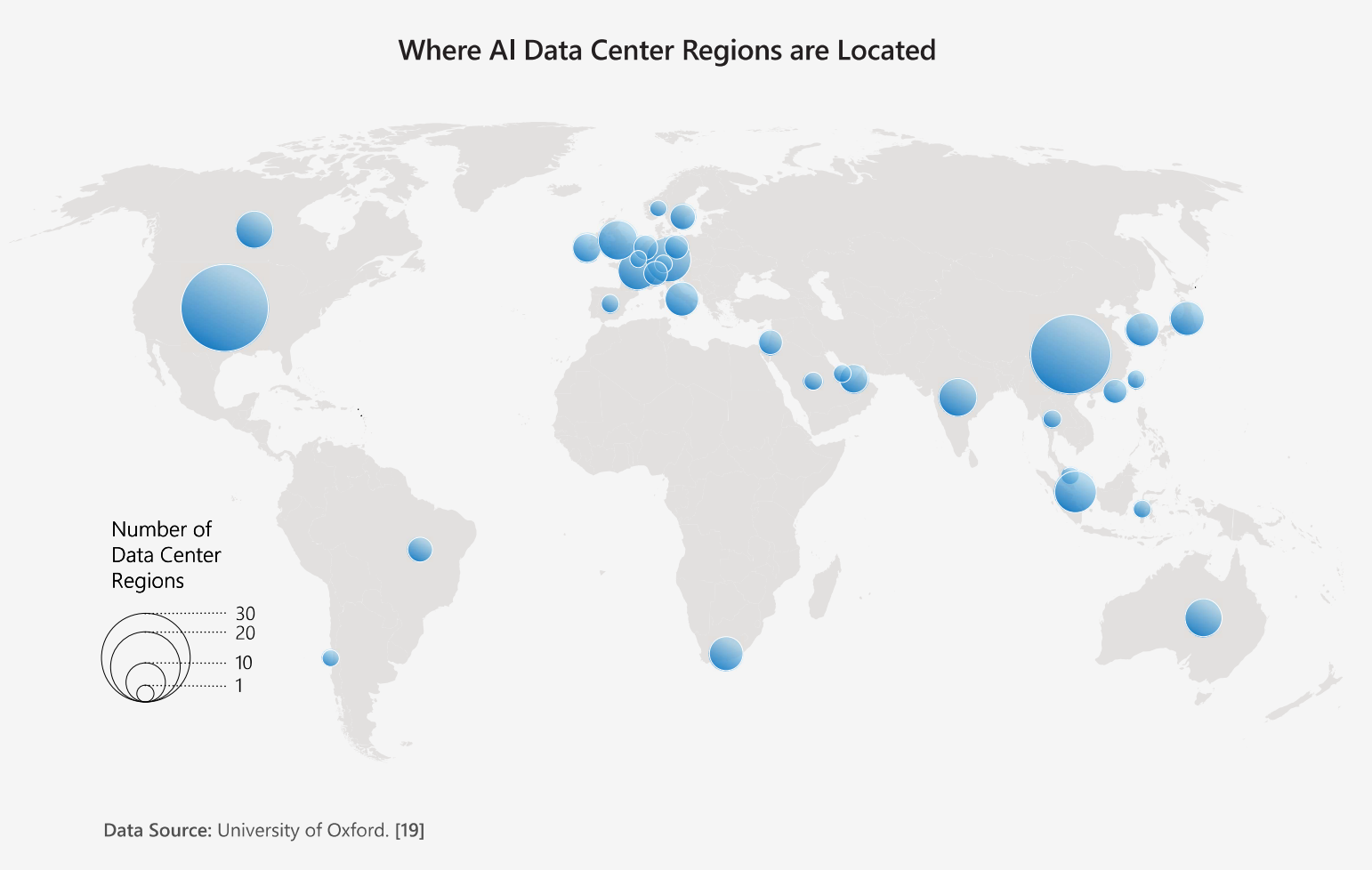

Most developing countries will be left out of the AI boom in other ways, too. Much of today’s data center investment is happening in wealthy nations that already have a strong foothold in the global economy. Developing countries have increasingly few levers to pull to enter the AI value chain.

Countries betting on digital services could have significantly less time to establish themselves and climb upward, representing a total upheaval of decades of economic planning. But regions that invested in manufacturing may also find their route up the economic ladder similarly stymied by AI.

Export-led industrialization has succeeded historically because bottom-rung manufacturing for products like textiles, food processing, and simple consumer goods required minimal upfront capital. Countries could enter with minimal technology and remain competitive through lower wages. The model was self-financing: profitability at each stage funded progression to the next level of development.

In the past, the technology disadvantage faced by new entrants into manufacturing sectors was modest enough that wage differentials still gave developing countries a competitive edge. Today, advanced manufacturing techniques increasingly demand greater infrastructural requirements for optimized production. These high capital requirements mean that cheap labor is becoming less important in modern manufacturing compared to factors like proximity to major markets and institutional capacity.

Increasingly powerful AI systems could exacerbate these trends by continuing to accelerate the improvement of manufacturing processes and making complex tasks easier to automate. For example, globally competitive garment factories are beginning to require AI-powered cutting systems and inventory management. Modern electronics assembly increasingly relies on automated pick-and-place machines and optical inspection systems. Many tasks previously left to human labor are now being exposed to automation due to improvements in AI.

As these cutting-edge processes become more capable, automated, and dependent on expensive capital, we could see the entrenchment of export-driven manufacturing among incumbents. Rather than bottom-rung industries transitioning to the next developing country every few decades, prohibitively high capital requirements might prevent countries with cheaper labor from competing.

/odw-inline-subscribe-cta

The winners could be existing manufacturers, who are already investing in modernizing their infrastructure even as their labor costs rise. The losers could be newly developing countries seeking to enter increasingly competitive industries. Bangladesh is a clear example: some experts predict that it could lose as much as 60% of its jobs in the garment sector in 15 years due to these trends.

A substantial factor in the success of the historical development ladder comes from a pattern often referred to as learning-by-exporting. Research shows that developing strong export industries can have multiplicative effects throughout an economy, in large part due to the development of local human capital.

First, workers gain the skills necessary on the job to compete effectively in a global marketplace. In manufacturing, this might happen via learning effective process optimization or quality control. In digital services, this could arise from developing English proficiency or strong international relationships. As these workers move on, they disperse their skills throughout the economy, creating new economic growth and increasing human capital.

Today, it’s too early to point to concrete evidence of AI’s impact on manufacturing. However, we have already been seeing trends over the past two decades that labor employment intensity has been on the decline for manufacturing, driven substantially by labor-saving technologies. Export industries are beginning to employ fewer workers — this leads to less knowledge diffusion, weakening the learning-by-doing that made export-led industrialization transformative.

If the diffusion of powerful AI systems into both manufacturing and digital services significantly accelerates labor-saving automation, we will almost certainly see further reductions in knowledge transfers. Over time, this would have compounding impacts on the long-term development of human capital and progression along the development ladder for developing countries.

AI automation could precipitate a crisis of labor across both developed and developing countries. Importantly, workers in AI-leading nations would not be immune from these dynamics. Early research suggests that domestic labor markets in wealthy nations may already be softening at the entry level, revealing a stark parallel between global development ladders and the domestic career ladder. Just as developing nations have historically relied on low-complexity manufacturing to climb the economic value chain, young professionals in the US rely on low-complexity entry-level tasks — “grunt work” — to build essential skills and climb the corporate structure. AI threatens to saw off the bottom rungs of both ladders simultaneously.

By automating these foundational tasks, AI could not only close the door on export-driven development in the Global South, but also hollow out the training grounds for the next generation of workers in the North. We could be on the precipice of a crisis of human capital — a world where both emerging economies and talent are denied the opportunity to develop the expertise necessary to compete.

Adaptation would be hardest for the Global South. Nations that hold a meaningful share of the AI value chain — whether through frontier model development, cloud infrastructure, or semiconductor manufacturing — retain policy options that others lack. They can, in principle, capture the productivity gains created by AI and leverage this wealth to support their affected workers. There are strong incentives for wealthy nations to maintain the stability and strength of their labor market.

Developing nations may not even have this option. Without leverage in the AI value chain, they may see an erosion of their export-led development strategies, without sufficient alternatives to support their labor forces. They may lose their competitive advantages in labor arbitrage due to AI without gaining sufficient leverage in return.

These countries are well aware of the uphill journey facing them. For example, 15 different African nations have published concrete AI strategies as of 2025, and an alliance of countries on the continent recently established a $60 billion fund to build domestic AI capabilities. Whether these efforts can generate enough momentum to vault these countries past the shaky rungs of the economic ladder remains uncertain.

—

AI may not slam the door shut for the Global South — but it will almost certainly force a strategic shift. The erosion of routine-task export advantages means that developing countries cannot rely on the industrial paths taken by earlier success stories. AI could erode the bottom and middle rungs of the development ladder, and it’s not clear that there are proven alternative strategies yet.

As we see the trends described above arising in the next decade, developing countries will have to look hard at their comparative advantages to understand the best path forward. They will have to develop their foundational digital infrastructure and find competitive niches in the emerging global AI value chain. Their most promising opportunities may begin to be more localized — domains in which individual countries have advantages in local knowledge, maintain a physical presence, or can provide context-specific data.

They may have to prioritize sectors where AI will remain a complement rather than a substitute for labor. Diversifying their economies toward more AI-resilient industries — such as healthcare, education, or tourism — may be an important component of their revised strategies.

Countries that can find nuanced opportunities to build new capabilities can and will find new routes up the economic ladder — but they need to begin confronting these risks now.

Thanks to Nick Stockton, Yolanda Laanquist, Danny Buerkli, Anna Yelizarova, Jackie Si Tou, Andrey Fradkin, and Ankit Mishra for their excellent feedback on this article.

See things differently? AI Frontiers welcomes expert insights, thoughtful critiques, and fresh perspectives. Send us your pitch.

Traditional insurance can’t handle the extreme risks of frontier AI. Catastrophe bonds can cover the gap and compel labs to adopt tougher safety standards.

The White House is betting that hardware sales will buy software loyalty — a strategy borrowed from 5G that misunderstands how AI actually works.